Dr. Jekyll, Mr. Hyde, and the Hidden Splits of Trauma and Addiction—Releasing Through the Body

- Dr. Kat

- Aug 21, 2025

- 7 min read

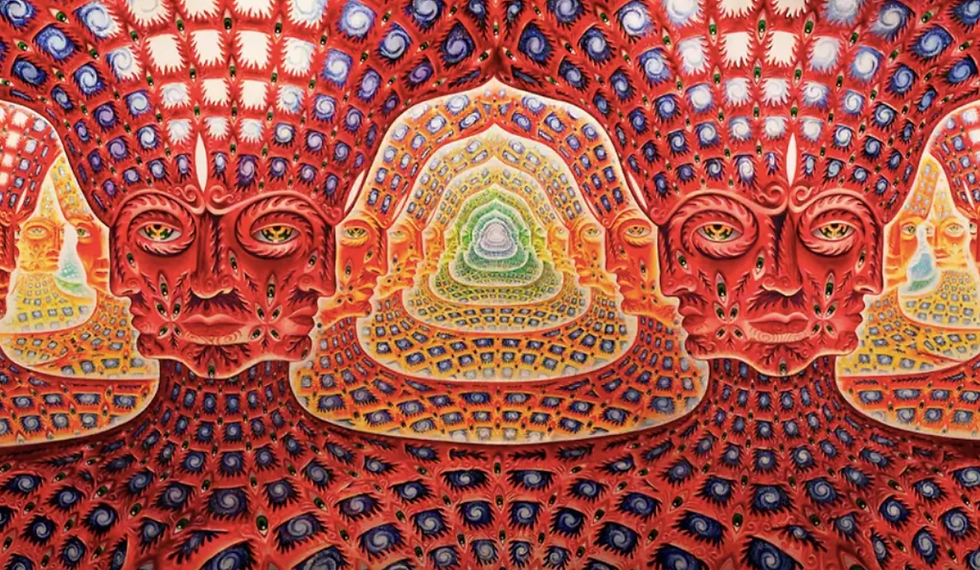

Have you ever felt like two selves are living inside you? Perhaps you present one version of yourself to the world—measured, capable, calm, and resilient—while another, hidden self emerges in moments of craving, impulse, self-sabotage, or collapse. This experience can feel bewildering, even frightening, as though something foreign has taken over.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is more than a gothic horror story. It is a profound allegory about the divided human psyche. Its enduring power lies in how vividly it captures the inner conflict between our socially acceptable self and our hidden impulses. For trauma survivors and those navigating addictions, this metaphor speaks with unsettling precision.

Philosophers have wrestled with the paradox of the divided self for millennia. From Plato’s tripartite soul, to St. Augustine’s confessions of inner conflict, to Nietzsche’s critique of repression, the tension between light and shadow has always been part of the human condition. What modern trauma research and somatic therapies like Peter Levine’s Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma add is a new understanding: these divisions are not just moral or existential—they are embodied, physiological realities that live in our nervous systems.

The Duality Within: Trauma Splits as Inner Jekyll and Hyde

In Stevenson’s novella, Dr. Jekyll is a well-respected gentleman who longs to separate his virtuous self from his darker impulses. He creates a potion that allows him to become Mr. Hyde, a figure unrestrained by morality or social expectation. At first, Jekyll feels liberated. He believes he has found a way to keep his darker side hidden while maintaining his respectable life. But soon, Hyde grows stronger, more violent, and more uncontrollable. Eventually, Jekyll loses the ability to choose when the transformation happens—Hyde takes over at will.

This story resonates with what I’ve described in my blog on mild splits in sexual trauma survivors. When faced with overwhelming pain or violation, the psyche often protects itself by compartmentalizing. One part of the self continues to function, go to work, care for others, and present a socially acceptable image. Meanwhile, another part carries the unbearable weight—memories, emotions, shame, and survival impulses.

Like Jekyll’s potion, splitting can feel adaptive at first. It allows survivors to keep moving, to survive unbearable circumstances. But over time, these splits create instability. What is buried does not disappear—it festers. Eventually, it erupts in behaviors or symptoms that may feel alien, frightening, or destructive.

This dynamic echoes Plato’s tripartite model of the soul: reason, spirit, and appetite. Plato argued that harmony requires balance between these parts. When appetite dominates, chaos ensues; when it is entirely denied, it grows more dangerous. Stevenson’s Jekyll is Plato’s rational man trying to suppress appetite, only to have it return in monstrous form.

St. Augustine described the same paradox in his Confessions. Reflecting on his youth, he prayed: “Grant me chastity and continence, but not yet.” He wanted virtue, but also indulgence. This divided will mirrors Jekyll’s wish to be both saint and sinner at once, and it reflects the same psychic split trauma survivors often feel—wanting to appear intact while another part yearns for relief at any cost.

Repression, Shame, and the Cycle of Addiction

Jekyll’s downfall comes not from Hyde’s existence, but from his refusal to integrate him. He represses what he deems unacceptable and tries to sever it entirely. But as Nietzsche warned, what we repress doesn’t vanish. Instead, it grows in power and returns in distorted ways.

For survivors of trauma, repression often takes the form of silence and shame. They may tell themselves:

“If I let myself feel this grief or rage, I’ll fall apart.”

“If I show others this side of me, I won’t be loved or accepted.”

To survive, they push these parts underground. But what is exiled doesn’t disappear. It resurfaces in self-sabotaging choices, compulsions, and addictive patterns.

This is where Aristotle’s idea of akrasia—weakness of will—comes in. Aristotle asked why people act against their own better judgment. He observed that desire and impulse can overpower reason. Addiction is perhaps the most painful expression of this: knowing what is destructive yet being unable to stop, as though another part of the self has seized control.

We can see Jekyll’s progression mirrored in the cycle of addiction:

Experimentation: A behavior begins as a way to feel relief or escape.

Dependence: The behavior becomes the go-to coping mechanism.

Loss of Control: The behavior takes on a life of its own, surfacing without conscious choice.

Collapse: The self fragments under the strain.

This is Jekyll’s arc, but it is also the lived experience of many survivors. Addiction becomes Hyde—the shadow self breaking through, demanding release, regardless of cost.

The Body Speaks: Somatic Experiencing as the Path to Integration

While philosophers explored these dynamics in moral or existential terms, modern trauma therapy places them squarely in the body. Peter Levine’s Waking the Tiger revolutionized trauma healing by showing that trauma is not just a memory or story—it is energy trapped in the nervous system.

Animals in the wild endure constant threats, yet they rarely develop chronic trauma. Why? Because after a life-threatening event, they discharge the energy through shaking, trembling, or movement. Their bodies complete the survival cycle. Humans, however, often override this instinct. We freeze. We shut down. We hold it inside. The body never finishes the response, and the energy becomes trapped.

Over time, this stuck energy expresses itself as anxiety, depression, compulsions, or addictions. These are not failures of morality or willpower. They are the body’s desperate attempt to resolve what was never completed.

Here, Levine’s work intersects powerfully with Carl Jung’s concept of the shadow. Jung taught that the denied parts of the psyche must be faced and integrated, or they will sabotage us from the dark. Levine shows us how to do this somatically—by listening to the body, tracking sensations, and allowing discharge, we invite the shadowed parts back into wholeness.

Kierkegaard described despair as “the sickness unto death”—the condition of being out of alignment with oneself. This is exactly what trauma creates: a self divided against itself, fragments cut off from one another. Healing is not about destroying Hyde, but about reuniting Jekyll and Hyde into a single, embodied self.

Practical Ways to Heal the Split: Applying Levine’s Insights

Levine’s Somatic Experiencing (SE) offers practical tools for reintegration. Here are six accessible practices to begin exploring:

Track the Felt Sense

Pause and notice what is happening in your body right now. Tingling? Heaviness? Warmth? Numbness?

Ask: Where in my body feels tense? Where feels calm or neutral?

Why it helps: Trauma cuts us off from body awareness. Tracking sensations reconnects us to the body’s subtle language, allowing us to catch activation before it escalates into destructive behavior.

Pendulation

Focus gently on an activated place (tight chest, restless hands).

Then shift attention to a calmer place (feet, breath, or a hand resting on your lap).

Move awareness slowly between the two.

Why it helps: Instead of being stuck in repression (Jekyll) or overwhelm (Hyde), pendulation teaches the nervous system flexibility.

Micro-Movements for Completion

Ask your body: What small movement do you need right now?

Allow your shoulders to roll, your legs to push lightly into the floor, or your body to tremble.

Welcome yawns, sighs, tears, or laughter.

Why it helps: These are signs of discharge—your body releasing stuck survival energy.

Orienting to the Present

Slowly turn your head. Look around the room.

Let your eyes rest on objects, colors, or textures.

Whisper inwardly: I am here. I am safe now.

Why it helps: Trauma keeps us stuck in the past. Orienting gently re-engages the parasympathetic nervous system, grounding us in present safety.

Resource with Safety Anchors

Bring to mind a safe person, place, or memory.

Notice how your body responds—softening, warmth, slowing of breath.

Why it helps: Resources provide the stability to face hidden parts without being overtaken.

Allow Gentle Discharge

If trembling, warmth, or tears arise, let them flow.

These are not signs of weakness—they are signs of completion.

Why it helps: This is the body’s catharsis—release that restores balance.

Somatic Integration Exercise: Meeting Jekyll and Hyde Through the Body

Here is a full guided practice combining the Jekyll/Hyde metaphor, philosophical insight, and Levine’s body-based healing approach.

Step 1: Settle and Arrive

Sit or lie comfortably.

Look around and name a few colors or shapes.

Feel the support beneath you.

Ask: Right now, am I safe?

Step 2: Invite Both Selves

Imagine your Jekyll self—calm, capable, controlled.

Imagine your Hyde self—impulsive, hurting, craving.

Whisper inwardly: Both of you are welcome here.

Notice where each shows up in your body.

Step 3: Track the Felt Sense

Focus on tension or discomfort.

Then shift to a calm area.

Move gently between the two.

Step 4: Micro-Movement and Release

Ask your body what it needs. Allow shaking, stretching, or sighing.

Welcome any natural discharge.

Step 5: Anchor in Resources

Imagine a safe person, place, or memory.

Wrap both Jekyll and Hyde in this safety.

Step 6: Closing Reflection

Thank both parts for showing up.

Whisper inwardly: I am learning to be whole.

Reorient gently to your space.

This practice is not about erasing Hyde or clinging only to Jekyll. It is about learning to hold both, allowing the body to integrate what was once divided. Over time, this strengthens the nervous system’s capacity to be whole.

Healing Is Wholeness Through the Body

The tragedy of Jekyll was not that he had a shadow, but that he believed he could banish it. Philosophers from Plato to Kierkegaard warned that division within the self breeds despair. Nietzsche and Jung reminded us that denied parts always return. Levine shows us how the body carries this same truth: what is suppressed must eventually surface, and healing means allowing the body to complete what it never could.

Addictions and destructive behaviors are not moral failures. They are signals—Hyde’s way of demanding attention. They are the body’s attempt to release trapped energy, even if in distorted ways.

Healing comes not from repression, but from compassion. Not from silencing Hyde, but from listening to him. Not from erasing shadow, but from welcoming it back into the circle of self.

Stevenson’s tale is a warning about repression. The philosophers give us language for divided wills and shadows. Levine gives us a somatic pathway home. Together, they remind us: wholeness is possible. When we stop running from Hyde, we discover that he carries not only pain, but also vitality—the raw life force waiting to be reclaimed.

Comments